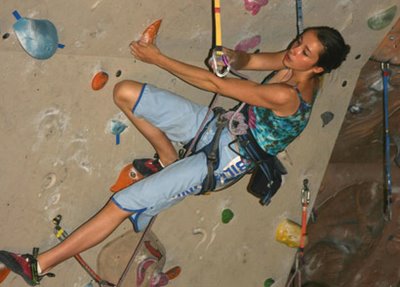

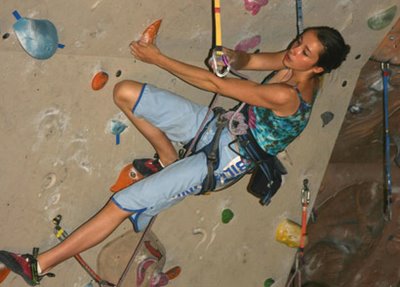

From one Berry to another... I’ve had the privilege to interview one of the UK’s most successful young climbers on the indoor climbing scene (and she’s only 14!). Natalie Berry has already been a British champion five times and with her most recent successes on the international competition circuit, she has established herself as one of our most successful competition climbers of recent years. It’s obvious from watching Natalie in action that she has potential to take this ability much further. And I think its even clearer after reading her answers to my questions below that she has the single minded determination to turn potential into reality. Combining a mix of a great attitude like Natalie’s with good training and support at the right time is like mixing magic – its really powerful. So I think most of us have something to learn from her, even if its just sharing a little of that determination…

Natalie Berry

OCC: What age are you now Natalie and how long have you been climbing?

Nat: I am 14 years old and I have been climbing for 6 years – I started by chance when I visited a shopping centre in Glasgow where there was a mobile wall outside!

OCC: What are your best achievements so far in climbing and what are your goals for the future?

Nat: My best achievements so far have been coming 4th in the World Youth Championships in Austria in August 2006, and becoming five times British Champion (The BRYCS, BBC twice & BICC, twice). I aspire to be both European and World Champion in the next few years!

OCC: Tell me about your climbing motivation – why do you climb and how important is it for you? Do you think your climbing motivation has changed any since you started?

Nat: I find it quite easy to be motivated for most things in life – I am driven by a burning desire for success. I climb because I enjoy the freedom of movement and feeling of power that the sport gives me. I also enjoy the fitness – both physical and mental – that I have earned over the years. The mental science of climbing is particularly interesting to me – whether I’m in a competition or simply in training, I find it very interesting psyching myself up to climb, articulating movements and co-ordinating techniques.

OCC: How much training do you do? Do you separate climbing for fun and training, or are they one and the same? Tell me about the elements of your training – what activities do you do?

Nat: I climb four days a week. I incorporate anaerobic training (forearm endurance), some circuits, on-sighting, red-pointing – a mixture really. My training schedule is organised around my events calendar, but I often just follow my instincts and do what I want. I have found that I respond quickly to intense training and enjoy working hard to achieve my goals. I also do pull-ups and other climbing-specific training at home each day. I believe success is 90% hard work and 10% talent.

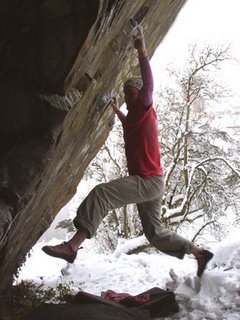

Natalie training in Imst

OCC: Lots of female climbers are put off or struggle with steep climbing and powerful or bouldery moves. Is this a limitation for you? If so how have you tried to get round it or work on it?

Nat: I have very strong static lock strength and so I therefore often use it to my advantage! Because of my build I have had to work on power, particularly as most international competitions take place on steep, powerful routes – unlike those in walls here in the UK!

OCC: Do you have any elements of your training that you find a chore? I remember reading a article by Marc le Menestrel talking about how he tries to find ways to get to like his dislikes in climbing or training, and that this really helped him progress. Can you relate to that or do you just like everything about climbing!?

Nat: I am lucky in finding training fun – most of the time – and I have great friends whom I see regularly down at the wall and can climb with, making training even more enjoyable. There are days, however, when I have to motivate myself when I’m feeling low! I use competitions and other big events to psyche myself up. Sometimes I just have to remember how it felt the last time I was climbing well, and I push myself to get back up to where I was before.

OCC: Describe your climbing style. Do you think your natural style is good for steep indoor routes or have you had to alter it in any way (i.e. movement pattern, climbing speed etc…)?

Nat: Technique has always been my strong point. I believe I am a very natural climber – I have a good store of engrams in my mind! I have quite a slow climbing speed, so on steep routes I really need to learn to climb faster. I prefer technique over power and I particularly enjoy really crimpy, fingery routes that many strong male climbers can’t do!

OCC: How do you fit all your climbing in with the other things in your life like study and social stuff?

Nat: I always strive for success, so find it quite easy to make time for my schoolwork – I am the Junior Proxime Accessit of my school. I think it is important to show the same care and devotion in all aspects of life – whether it be in sport or academically. My social life is my climbing life really – as I said before I have so many great friends all around the world. At home in Glasgow my climbing friends are really supportive and I enjoy helping them and others with their climbing too.

OCC: You specialise in indoor climbing – How important do you think it is that you train at a good climbing wall? What do you look for in a good climbing wall; big steep routes? a good scene? Other things?

Nat: I think it is incredibly important to train at a good climbing wall – all you have to do is look at the results the European juniors (and seniors) are achieving on the international competition scene, and then visit a few of their walls and understand why! It is not necessarily true that they are simply more talented than other competitors or that they “train better”, but their success – to me – seems to grow from the World-class facilities that they train on. I spent two weeks training in Imst, Austria – where the World Championships were held – prior to the competition. I realised just how beneficial it would be to have such a facility here in Britain. Climbing at Imst is like playing vertical chess. You have to weigh up the steepness of the wall - 45 degree pillars with numerous bulges and roof sections – as well as having to clip many 2 foot long quickdraws, on all 18 metres! I saw countless children from about the age of three or four and above top-roping– and maybe seven or eight year olds leading through the steepest sections of wall. From that moment I realised just how different the foreign attitudes towards climbing are from those here in the UK –start the kids young, encourage them, add some fun and watch them win.

OCC: What do you think is holding you back from getting even better results in comps than you get now?

Nat: I definitely think that the major ingredient missing from my training here in the UK is a European-style training facility – if we want British competitors on the international podium then this appears to be the way forward. I just wish I could have the funds to train abroad if we can’t have the facilities here. I would like to sport climb outdoors more but due to time and financial restraints I am quite content with focussing on indoor climbing for now!

OCC: What climbers most inspire you and why? Having competed on the international circuit what things have you learned from climbers around the world?

Nat: I am inspired by many climbers – not just world-class athletes but also beginners and climbers I’ve met of all ages and abilities – after all “the best climber in the world is the one who is having the most fun”. Neil Gresham has given me a lot of support and encouragement – I admire the positive attitude which he brings to the sport. Angela Eiter of Austria has also impressed me with the array of international competition titles she has won. All of my climbing friends (many of whom I compete against) inspire me too – I love learning from other people and find it very interesting studying their styles and techniques in training and competition. I think it is so important to learn from others and equally that they learn from you; everyone is unique in their climbing, both mentally and physically. I think I’ve learned a lot about life from my travels and competitions – I believe I’ve attained a lot of wisdom from meeting different people of all backgrounds and personalities from all around the world. One common factor I have noticed that bonds all the competitors at a competition is a love of climbing – a desire and determination to succeed, no matter what. After all, out of dreams comes determination, and out of determination comes success…

Natalie has managed to align enjoyment of the process of climbing and training to a clear goal for what she wants to achieve. In this way, more work and dedication equals more fun. This interview raises the important point of what outside support do climbers need to get to where they want to go? In Natalie’s case, she needs access to high quality training facilities to compete at the level she is capable of. As we don’t have steep enough climbing walls in Scotland just yet, this means travelling, which takes money. In most other people’s case, outside support might be as simple as reading some training advice like this website! Natalie has already gained some sponsorship from

Scarpa,

Glasgow Climbing Centre,

Entreprises and

Cotswold, but found it hard to secure the levels of support she needs and is hoping to find new sponsors. A familiar story for top climbers. She’s been a nominee for the young sports person of the year, a regional award that eventually went to athletes from Olympic sports who were not selected for international competition like Natalie! Olympic sports are being targeted for encouragement in the UK at the expense of all others right now, for

obvious reasons.

This is an interesting subject which I’ll talk more about in future posts. I am no expert on making a living out of climbing although I have been trying myself for a few years. My experience is that the climbing industry is simply too small for most companies to afford the levels of support it takes for an athlete to succeed. The solution? Well there isn’t an easy one. I guess the most productive way for climbers who want to gain sponsorship is to take ownership of the problem of the size of the sport and use their experience and status to promote it to help the sport grow in whatever mediums they choose. Ultimately, giving the sport a higher profile will benefit everyone. More on this later…

Thanks for talking to me Natalie, keep up the determined approach and the results will keep coming! Click here to see

Natalie’s website.

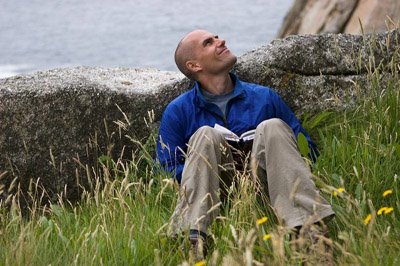

Will Gadd enjoying Ben Nevis - straight talking is what you need when you want to break out of a rut and improve, Will comes through for us!

Will Gadd enjoying Ben Nevis - straight talking is what you need when you want to break out of a rut and improve, Will comes through for us!