31 August 2006

Training for climbing books

Home training facilities - direct comparisons

Bouldering Wall

Pros: You can work on strength or endurance, but all the time you are doing whole climbing moves and thus learning technique. Its also much easier to cover and target all aspects of strength you need to work on (e.g. pinches, big moves, undercuts etc).

Cons: Takes up a lot of space. You might end up trying to use it to solve all your climbing weaknesses (which it won't!) and become a super strong wall rat with no technique or tactics.

System Board

Pros: If you already do a lot of real climbing and thus your technique gets lots of work, a system board might be more effective for working on strength. Especially useful for training for a specific type of climbing (e.g. Frankenjura pocket routes). More measurable than bouldering for improvements.

Cons: Again, becoming addicted to it and overusing it at the expense of other training priorities.

Campus Board

Pros: Very effective for gaining strength on big moves and small holds. Doesn't take up as much space as a wall.

Cons: Only useful if you already climb a lot and if used as a supplement, NOT SUBSTITUTE, for this climbing. It can subconsciously alter your technique away from a reliance on footwork if you let it.

Fingerboard

Pros: Takes minutes to set up and takes up no space and no money (mine cost less than £10 to make and install). You can put it wherever you spend the most time so you can get steely fingers while watching the box, working, whatever. Easy to build into a busy routine because the sessions are so short - just about everyone can find half an hour in their day.

Cons: It's boring if you don't play music, watch telly, chat to folk or work while your doing it.

Weights

Pros: Can be stored away.

Cons: Can waste your time by working muscle groups that are not weaknesses in your climbing and taking your time away from learning climbing technique. So only really useful for people who already do all of the above or have some significant lack of body strength in a specific muscle group.

Time poverty and ways round it

For people without many years of climbing behind them and those climbing at lower grades, increasing the number of climbing moves you make each year is often top priority. There is no point being 5% stronger if you don't have technique with which to apply it. For those who move very well on the rock and have tactics very well sussed, strength is more likely to be the biggest barrier to the next grade.

But there are 2 more points to bring up here:

1. If your routine (and time available to climb) changes during the year you can use the busy times to build in some strength training (preferably boulder supplemented by some basic strength work). This works well because busy times tend to be quite regimented which makes it easier to discipline yourself to spend a session doing organised strength training. Also strength training takes the least training time - short, high quality sessions are exactly what youre after.

2. You need to find ways to spend your time efficiently too. Do you spend ages travelling to a wall? If so build one in the garage, or if you have a tiny flat like me just put up a fingerboard. If you want/need to use big climbing wall for routes and to meet friends then you could do a half hour session on the fingerboard before going there. When you arive you'll already be warmed up.

If your routine is just busy all year round and those two sessions are all you've got, then stick to training that involves actually climbing. But I feel most people can squeeze in very short additional sessions somewhere in their week, to work on basic strength as a supplement. For instance I fingerboard when I have reading to do (I work from home). Others will do half an hour at lunch. Others will put the fingerboard above the kitchen door and do a few hangs every time they are boiling the kettle!

29 August 2006

Many questions in my inbox!

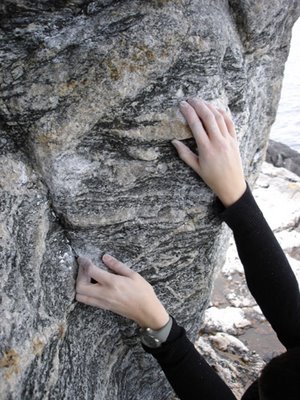

The body is moving, but the finger flexors are contracting isometrically while hanging from the holds.

The body is moving, but the finger flexors are contracting isometrically while hanging from the holds.I've been really overwhelmed with the response to this site and my inbox is flooded with questions and ideas from you. Thanks! I will get round to answering them all and posting up the articles you've asked for, but I've had a great many so please bear with me!

Connor asked:

"For a long time now I have been questioning the effectiveness of training finger strength through traditional training techniques like deadhangs, finger board workouts, etc. All these exercises rely on applying weight to a static hand position, crimping for instance, until failure. But how effective are static isometric contractions for training strength? Other resources on general strength training I have read reject this type of training because it is relatively ineffective compared to engaging the muscle over a range of movement. If I were going to train my chest muscles, I would never just hold the bench press bar in a static position until I was tired. I can't figure out why exactly we train our fingers and forearm muscles this way. The flip side to my thinking is that climbing basically involves a series of isometric finger contractions to get up a route, so is this training simply sport specific, therefore effective?"

Connor has really answered his own question at the end. This comes down to the basic principle of specificity - you get good at what you do. Most sports require using a muscle through a proportion, or all of its range of movement and in a dynamic (moving) contraction rather than isometric. So mimicking this in training is needed. But with climbing we hang isometrically (isometric means the muscle is producing tension but not contracting - i.e our fingers stay still on the holds) from holds so must do this in training too. Of course we use different muscle lengths in the different grips (crimp, openhand etc) so this also has to be done in training because the carryover of strength at one muscle length is limited at another. So stick to the hangboards!

Isometric contraction is actually surprisingly rare in sport. Endurance of isometric contractions, or more specifically, intermittent isometric contractions in the case of climbing is very interesting from a physiological point of view because of the effect of the high intramuscular pressure on blood flow inside the muscle. There is some interesting research on this in the fields of dingy sailing (yes I know, I was surprised too!) and motocross (also a forearm fatigue issue in this sport). More on this later...

17 August 2006

Climber interview - Neil Gresham

OCC: Neil you're probably the most experienced climbing coach in the UK, and since climbing is still a young sport in its stage of development, you've had the opportunity to influence many of the trends in training for climbing. Can you pick out one or two key messages that you've tried to get across to climbers over the years that stands out as most significant and/or innovative?

Neil: I guess the most obvious one is that it’s hard to persuade climbers to plan, but if you can convince them to use the principles of periodisation as a guideline for their training then they’re going to climb so much better and be less likely to get injured. The other big one regarding technique is that you have to focus on style and looking good (yes, I know it goes against the grain!) rather than getting to the top at all costs. People find it hard to be mentally aggressive and physically relaxed at the same time, but that is exactly the state you are aiming for.

OCC: The first climbing magazine I ever bought has an article on redpoint tactics written by you, and I still refer to it occasionally now. Is there any piece of advice or writing from your early days that still keeps you on the right track today?

Neil: Yes, for sure, a classic example is the difficulty of getting both strong and fit at the same time seeing as they require such contrasting approaches. I once wrote a piece for OTE in the early 90s which described the requirements of stamina training as being quantity based and the requirements of power training as being quality based. Bouldering work-outs should be short, intense and with good rests in between, whereas stamina sessions should be long slow-burners with as little rest as you can get away with. If you want to develop both at the same time then you need to prioritise one for a while and then switch to prioritizing the other rather than going hammer and tongs with both. There are so many little rules that help out when it comes to coordinating strength training with endurance. For example, if you’re training 2 days on then it’s nearly always best to train strength on the first day, and so on. Another good general principle is that the best time to back off with your training is when things are going well, and this is of course the time when you are least likely to want to. That one has probably saved me from injury countless times.

OCC: I think it's fair to say your notoriety as a climber really took off when you moved beyond the hard sport climbing scene, started doing routes like Indian Face and generally became a super all-rounder. Do you think your attitudes to training and preparation helped you do this, or was it just your sport climbing fitness?

Neil: It was both. Sport climbing gives you a huge buffer for trad in terms of strength, endurance and technical ability. It’s clearly more of a chance game if you turn up at the base of an E9 knowing that F7c+/8a is your limit. It’s only the total headpointing gurus like Nick Dixon who can pull this off. But then it’s people like Dixon, Dawes and Grieve who are the masters of the preparation side and who taught me so much. None of these guys are really strong climbers but they developed a whole new way of looking at bold climbing. Parallels were drawn with the Samurai warriors who had to practice highly complex routines, knowing that the penalty for a mistake would be serious injury or death. Many of the tactics that have been coined both for preparation and for coping with mid-ascent catastrophes are pretty zen-like in nature. It’s a vast subject but the essence of it is to focus so hard on the delivery of spontaneous action that there is no space left in your brain for disrupting thoughts or emotions. There are a few lucky climbers who can turn this on straight away with minimal experience to draw on, but for me it took years to nurture. I was very timid when I started climbing.

OCC: It’s always seemed to me that 'natural talent' in sport can sometimes bring problems as well as benefits. Many climbers who have the most prolific careers have had rather ordinary abilities to start with that have catalysed a determination and work ethic that goes on to surpass the natural talents (who get too used to success without effort). Do you agree with this? If so, do you try to develop determination in your coaching and in your own climbing?

Neil: I couldn’t possible agree with this any more. So often the most talented climbers, especially the young ones are total slackers. In short, they don’t appreciate what they’ve got because they haven’t worked for it. There is nothing like being fundamentally un-talented to make you realize that you have to capitalize on the fleeting moments when you feel that you might be in with a chance. This ethos has defined my entire climbing career. It means that your finishing game becomes your strongest weapon. Can it be coached? Indeed it can! Let’s move away from nonchalant teenagers and look at keen but less-experienced adults – many just don’t know hard you have to try. It was Sean Miles who once told me that one of the big things that goes wrong with his climbing after a break is that he forgets how much effort you need to put in. This statement holds true both in the present sense (mid-climb) and also with your overall approach to training. Look at Rich Simpson and Chris Cubitt – these guys have sweated blood for it. The right attitude can be nurtured with anything from the use of key words as metaphors to tougher goal setting. There are all sorts of devices.

OCC: One issue that is often on the training climber's mind is body shape and how to best manipulate it. What have you learned about this in your experience? Do you think it is best to work with the frame you've got or become either a Dave Graham or a Malcolm Smith?

Neil: I think the answer is hidden in the question by the fact that you picked both those two climbers. They are both at the very top level and yet they have very different frames. It’s elementary stuff: to climb well you need a good power-to-weight ratio. Graham gets there on weight (or lack of it) and Smith gets there on power (or surplus of it). If you’re both heavy and weak then you’re not going to do very well. When Malc did Hubble he was both strong and ridiculously light but it was unsustainable and the combination of the dieting and the training nearly broke him. So long term he has settled to be strong, a little heavier and a lot happier! If you’re naturally a stockier build then you simply have to ask yourself how much you want it and how far you’re prepared to go. It’s easier for lighter framed people as they don’t have to think about all this! That said, a little extra muscle is a good thing for bouldering but for routes it only serves to weigh you down.

OCC: Can you describe roughly what elements you think would be involved training wise, if a climber set a goal of onsighting E9?

Neil: Are you asking for a bit of coaching advice here Dave?! After all, you’re one of few in the UK who’s in with a chance. Firstly I think this is a young man’s game. Leo Houlding was a contender when he was full of precociousness but he got older and worst still he became famous. I think it’s pretty important to still feel that you have something to prove, preferably just to yourself. James McCaffe was (and still is) another candidate. He has a very genuine love of climbing that isn’t media-driven and a high level of talent, but he got that big scare when he went off-line on Masters Wall and I think that really brought it home. It only takes one near miss to make you realize that the confidence building game we play is partly based on delusion. There are a few young lads who I’d like to mention here but to do so would be putting them at risk. If the media start rallying round with something as sensitive as this then the motives become cloudy and it gets even dicier. Back to the question – you need to be climbing outdoors a ridiculous amount and hence would probably have to give up any full time employment for up to 6 months. Here’s what I’d do if I was remotely in with a chance. Go to Europe in the winter and not come back until I’d onsighted 6 or 7 8as and 2 or 3 8a+s. Stop in Font on the way back to get my strength and technique back up and make sure I could flash Font 7cs and do 8as easily in a day. Do loads of onsighting all-round the UK in the spring, starting first with the safe, strenuous ones and then progressively moving on to bolder ones. I’d make sure I’d done a grade pyramid of 1 or 2 ground-up E8s, 6 or 7 E7s and well over a dozen E6s. All these routes would be in a full variety of styles, but then I’d pick my E9 and start focusing purely on that style. Then I’d start mental prep for the 9 and maybe do a few up-&-down style recces on the route. You know the rest. All yours, Dave!

OCC: As you know all too well, trad climbing in the top end E grades is a genuinely dangerous business. How do you decide you are ready to go for a lead you know will be at your limit with real consequences if you make a wrong judgment? What do you think it takes to walk away from a route when doubt creeps in just before you are about to lead it? Harder still, how do you coach these skills?!

Neil: My doctrine here is that there are two voices – the one in your head and the one in your guts, let’s call that one your sixth sense. If you ever let your rational mind over-ride the ‘sixth sense’ then you’re playing a dead man’s game! This may sound wooly and superstitious but if you don’t know what I’m talking about then you simply need to go out and do more trad climbing. Backing off teaches you the parameters and when the sixth sense says ‘go’ then you’ll trust it. But if you haven’t nurtured that inner voice tenderly over time then you have no referral device for your decisions. It’s like a final check: brain says ‘yes’, sixth sense says ‘yes’… ‘off we go then’. On the day I fell off Meshuga, everything was perfect on paper, conditions, skin, preparation, the lot. But something irrational inside me said ‘don’t do it’ and I chose not to listen. Never let your the to get it over with get the better of you. Be quiet, cut through the butterflies and the eternal chattering of your mind and listen to what your inner consciousness is really saying. And if it’s really saying ‘no’ then don’t go - an amber light is the same as a red one! You’ll know when the time is right.

OCC: Who in climbing have you seen or coached over the past few years that has really impressed you? What can we learn from their approach?

Neil: Natalie Berry has really impressed me and I wish I was able to do more work with her. There are climbers three times her age who’ve been climbing three times as long who haven’t worked out half of what she’d sussed by the age of ten. She has a rare grasp of the movement, her tactics are impeccable, she knows how to train and how to learn from her mistakes. To be honest, so many climbers impress me – Ben Moon for being so relentlessly good, Rich Simpson and Steve Mac for taking over where Ben left off so many years ago with sport climbing, Paul Craven for constantly re-inventing his climbing by switching styles, Charlie Woodburn and Matt Birch for over-coming debilitating illnesses and cranking to ever higher levels, you (Dave Mac) for being out there on your own and pushing both headpoint and Scottish winter standards, Oh and Ryan Pascall as a young climber who seems to know what to do with his talent. And also at a much more modest level, there are a few people who I’ve coached - there’s a chap called Paul Bate who’s in his late 40s, with a family and a who holds down a very demanding and high-flying position in the world of finance. On our first session he said to me ‘Now then Gresham, I don’t want any creepy bullshit from you – I pay you to tell me what I’m doing wrong, not what I’m doing right, so don’t spare me any punches!’ I slated him and he went from falling off 6a’s to onsighting 6b+ and redpointing 7a in 6 months.

OCC: I sometimes get the impression that climbing walls have generated a lot of impressively strong climbers, who try but don't succeed in matching this ability outdoors, especially on routes. For example, I was recently talking to a climber who's goal was to do Font 8a and French 8a, feeling that French 8a was the harder goal! What can climbers do to overcome this?

Neil: That sounds like crossed wires to me! Can it be true? I take your point that wall strength is easier to ‘convert’ than endurance because the head side of lead climbing usually sabotages things. However, the tactical side of both bouldering and sport climbing is pretty much the same outdoors as it is indoors. Converting the technique patterns of indoor climbing to rock is simply a matter of putting the time in. So what else can climbers do to overcome disparities? This depends on whether they mainly climb indoors due to time constraints, or whether they are cowering indoors because they are scared of the crag. The former climber will be super psyched when eventually they do get to the crag; however, they should still channel this motivation into skills acquisition rather than the short term desire to tick high grades. To the climber who is more timid, they need to ask themselves if they are genuinely scared of the crag or if it is more to do with their ego. If it’s a pride thing, then it comes back to ‘having a word with yourself’ (as Tim Emmett would say) and dropping the grade and going for mileage. Remember that the indoor and outdoor climbing grades will only equate for people who’ve put roughly equal amounts of time into both disciplines. Only push your comfort zone once you’ve established a base - this is surely the first thing any climber is taught. Regarding the specifics of crag skills – that’s too long to answer here. Sales pitch aside, have a look at my Masterclass DVD part 2!

(OCC: No really! No crossed wires! The psychological issue you brought up of being timid and feeling out of the comfort zone was what I was trying to get at with this question and example. I think that a lot of climbers aren’t sure how to go about training it)

OCC: The last one is a philosophical one: What is the benefit of getting good at climbing? Is it more enjoyable at E5 than HVS?

Neil: For me personally, I’d say that E5 is more enjoyable than V Diff or Severe but I wouldn’t say it’s necessarily more enjoyable than HVS. That depends on the quality of the route and a great HVS is surely better than a shit E5? I always used to look at Extreme Rock when I climbed in the lower grades and long to be pulling off proper moves on sheer faces rather than shuffling around on polished or vegetated ledges. For me there needs to be an element of exposure and technical intrigue and I can still find that on HVS. What you get from it seems to vary all the time – sometimes it’s the thirst for new experience in the form of increased mental or physical pressure that drives my climbing. But other times, if I can search out a climb that genuinely has something new and different to offer, then I don’t need to be pushing myself in order to obtain some value from the experience.

Thanks Neil! Neil’s masterclass DVD’s are a superb reference for just about all aspects of movement techniques and tactics for sport and trad climbing. A full review of these coming up soon. Check out Neil’s new site which has some great articles on training and tactics from climbers you’ll have heard of.

16 August 2006

upcoming climbing masterclass

15 August 2006

Climber interview - Lucy Creamer

OCC: You have onsighted on trad up to E7, which is still pretty much cutting edge in world trad onsighting. I think this is pretty remarkable since this is a lot nearer your physical limit than many of the men who have onsighted this grade. I know that a type of egotistical self-confidence can be used as a mindset to do bold climbing near your limit, whereas some people have a more confident but humble mental approach. What mental techniques or strategies have you used to commit yourself to bold routes? Do you think any particular style is effective or useful for female climbers in particular?

Lucy: One of my strengths in climbing is being able to push myself at my physical limit. It has always baffled me when I compare myself to others (in terms of pure physicality) as to why I can achieve harder onsight grades but as I said I think it has a lot to do with my mental attitude. When I get into physical extremis, I have the ability to override what is going on and push myself upwards rather than panicking and trying to retreat and or fall off. I generally only ever fall because I can actually physically no longer hold on.

I think climbing bold routes requires an inner self-confidence in your abilities and making tactical choices. i.e. I will never go on a route if I am feeling physically under par. For me one of the keys to climbing hard trad has been to do a lot of hard sport and therefore you know in the back of your mind you have the fitness to recover if you get in a pickle and get pumped and also you have the strength to pull off hard cruxes.

Lucy: This is a tough one. I don’t think it is that women are actively discouraged in climbing, I think it has more to do with British society and attitudes towards women and how we are brought up and what expectations are put on us.

Women are generally ‘looked after’ more by society, in a physical sense. i.e. if there is a group situation and there are some heavy loads to carry, it will always be the guys who are asked to do this job- the unspoken assumption is that women can’t cope with this type of activity- which is obviously rubbish.

Take this to a mountaineering environment, I can think of two good examples (of course there are many more) of women who have completely held their own; Louise Thomas and Alison Hargreaves. Speaking to people who have been on expeditions with both, these women were able to completely hold their own and generally perform as well as, if not better than the guys carrying loads etc. The pertinence of these two examples is that they are/were small in stature, not big bruisers. It definitely helps to be bigger in this environment but the point is they could still cope.

Sometimes, for the nicest possible reasons, women are not given the choice to do big physical jobs and I think this reinforces in their minds that they can’t. When in fact if they were a bit pushier, they would find they could. Maybe not at first, guys aren’t always good at things at first but with practice and time it would come.

OCC: You are really a big step above the level of other female all-rounders in the UK. What do you think are the main reasons why you’ve been able to dominate female all-round climbing in the UK for so long?

Lucy: Again, many reasons. One might be that over the years I have had many different climbing partners and have never had one person who has tried to look after me; I have always been independent and had to look after myself.

Right from the beginning, I wanted to do everything myself. I never wanted help on routes, I always wanted to find ‘my’ way of climbing it, even when I was seconding VS’s etc.

Also I have a strong inner confidence that has enabled me not to limit myself. So when I was only climbing E3, I didn’t sit back and think ‘oh well, that’s it’, I looked at others around me (generally always men) and thought well if they can do it why can’t I? So I would apply myself and work towards that next level.

I think women are not expected to be pushy or confident and therefore aren’t a lot of the time, it’s all about breaking ingrained attitudes and learnt behaviour patterns.

OCC: Steep bouldering and basic strength training are pretty essential for getting to high levels in climbing these days. This type of training tends to be popular with guys but not so much with female climbers - Do you think that’s true? Do you enjoy training for strength? If so, do you think you have a different mindset from many women climbers? Or do you not enjoy it but have just found a way to motivate yourself to do it!?

Lucy: Yes I do quite enjoy it. I used to do weights even before I started climbing, not full on hard-core pumping iron but just general stuff and it’s something I’ve always used. I’ve always been naturally quite strong, I could always do pull ups etc but I do have major strength weaknesses too and I think if you want to improve you have to work out what your weaknesses are and address them.

Lucy: As I said, I do weights regularly. I’ve never really got into campusing etc. Partly because I think I would break/injure myself if I went for it, partly because it’s hard-core and more so because I find I can make improvements doing other things I enjoy more. I’m sure if I had done more of this, maybe I would’ve improved quicker but I feel my body wouldn’t have coped with it very well (not very strong fingers and not the best strength to weight ratio for this style of training).

OCC: Who have been your role models in climbing and how much have they helped you? Have they been mainly male or female and is that just coincidence? Do you think it’s important for aspiring female climbers to climb and compare themselves to other female climbers, male climbers, both or does it not matter?

Lucy: I’m not sure I’ve consciously had role models, I don’t seem to work like that. I’ve been lucky enough to climb with many very good climbers over the years, like Ian V and Ben B and I’m sure I picked up things along the way but I tend to look at what I’m doing and work out ways to improve. I’ve always chatted to my peers about what they do and how they train etc but at the end of the day you have to find out what works for you through trial and error.

I think comparing yourself can lead you up a blind alley sometimes. It’s good to admire what other people are doing but as I said you’ve got to work out what works for you, we’re all different.

OCC: Female climbers have a disadvantage compared to males in terms of potential for developing strength, what strengths or advantages if any do you think females have that they can use to offset (or eliminate??) the difference?

Lucy: Yes we are at a definite disadvantage here. It’s interesting watching the juniors grow and develop; I’ve had some interesting chats with some of the young lads. You won’t see them for 6 months, the last time you saw them they were puny little weeds and then the next time you see them they are these muscle bound young men who can do 2 finger one arm pull ups on a pocket! They haven’t done anything different, sometimes they haven’t done anything, they’ve just grown muscles. This rarely happens to girls, you don’t wake up with muscles popping out everywhere and pulling one armers.

At this stage, the boys generally overtake the girls quite dramatically, mainly on steep stuff though. The girls just have to play catch up for a while trying to work on their strength deficits. I suppose an obvious difference is that girls really have to use what strength they have in a very economical way, which will generally mean developing a good technique (this is not to say guys don’t have or need good technique). Also, girls tend to work on their flexibility more and this can be a useful tool for ‘bending’ round hard moves. I think if you were a guy with all these attributes, it would be very hard for a girl to be better.

OCC: What do you think you need to do to climb even harder grades than you do now (assuming you want to!), that you aren’t currently doing?

Lucy: I spent the winter trying to improve my bicep and lower ab strength. These have always been two of my weak links. I was also working lock offs and reverse negs. All this combined has definitely made a difference to how I feel on routes. It’s made a difference to my grade but not a huge one. Making big gains at this stage is hard. However, I definitely feel better on routes.

I think I need to carry on with these weaknesses (when I go away on a months climbing trip, by the end of it those gains have pretty much gone, it’s a case of starting from square one again. Just going hard sport climbing does not, for me, work my particular weaknesses.

The other thing I could do, would be to wake up and miraculously have developed some power and be able to do one armers but that isn’t going to happen- oh well!

OCC: What other female climbers have inspired and/or informed you and why?

Lucy: When I first started doing comps, Fliss Butler was the queen of rock. I didn’t really know much about her as I wasn’t a big climbing magazine reader (I think it’s more of a guy thing) but she was an inspiration because she was awesome in the comps and on the rock, a woman after my own heart. And of course Lynn Hill, what can I say that hasn’t already been said. She’s pretty much one of a kind- you don’t get many Lynn Hill’s to the pound,

OCC: Finally, do you have any hard earned pieces of wisdom for female climbers that you wish you’d been told when you started to climb seriously?

Lucy: I can’t think of one nugget. But I suppose things like:

• Try not to let other people tell you what’s best for you, only you know what works for you and your body.

• Don’t be afraid to experiment, even if it feels like one step forward two steps back at times. Get in there and fall off boulder problems and routes, it’s the only way to improve.

• Have the strength of your convictions. If you want to work out your own way to do a move, do that. Find the inner confidence to tell your climbing partner to "shut up and mind their own business" (in the nicest possible way). What works for a 5’10” guy, will generally not work for a 5’2” girl.

• Girls, yes we are short, yes we are weaker. Unfortunately, that’s life, get over it. Try to work with what you’ve got. Get extra strong at locking off etc to gain height. There are ways round these things. But you do need to get stronger, if you want to push into the harder grades. We all know strength isn’t everything but it helps a lot.

• Finally, don’t let anybody tell you can’t do something, that’s solely your decision. Try to break the mould of deferring to men, be your own boss. I hope I don’t sound like a man hater because I’m absolutely not. But they will try to take charge of a situation, show them that you can look after yourself and your climbing needs. This is as much the fault of women as it is men. Be your own person.

Thanks Lucy and well done on your second 8b!

8 August 2006

For young climbers - case study

After three years of learning to boulder, mainly on my own, I got good at being pretty damn tenacious, and learned that the process of climbing stuff was actually the fun bit of climbing rather than the tick.

After three years of learning to boulder, mainly on my own, I got good at being pretty damn tenacious, and learned that the process of climbing stuff was actually the fun bit of climbing rather than the tick. I've been asking lots of young climbers what they would ask a coach if they had one and all of them asked me what I did when I started! So I'll briefly tell you what aspects of my start in climbing resulted in my best efforts since then.

One of the main blessings I had was to do a lot of bouldering on my own. I got really used to visualising moves in my head rather than just watching a mate try the same problem. Of course, you can learn climbing faster by watching good climbers, but learning to visualise moves in your head, and getting used to putting in a lot of effort into trial and error are very useful skills. Basically I developed a habit of looking at many different ways of doing a move I am struggling with, and being very open minded about the options. My attitude is that there is a way, it's just a matter of finding it. And finding it just means applying your mind more and being more patient and tenacious. It works!

Being able to climb hard on your own comes in very handy later on when you find your partners dry up for a while through circumstances. You have to be able to keep training or find other ways to keep your momentum up. Because I started on my own it just comes naturally to me now.

Training wise, once I started I worked fairly hard, but not hard enough. I used to climb indoors Monday, Wednesday and Friday and then outdoors at weekends. Indoors I'd warm up, do hard bouldering for and hour and a half, then ridiculously intense weights sessions for 2-2.5 hours, then back up to the wall for mileage problems for another hour, then sometimes a 30 min run to finish. I had a big tree in my back garden and I cut lots of holds in the bark. I used to run outside and climb my problems on it every ten minutes, every day! I did that for three winters when I was 16, 17 and 18 and my standard went from Font 6b to 7c. After that I went through a massive phase of getting injured fingers all the time, which I put down to poor diet, poor technique and choosing the wrong routes to try at the wrong time. Poor footwork and body awareness is probably the cause of most pulley injuries, along with poor warm-up or tiredness.

Injury got me into trad climbing and my climbing level took a massive leap because the volume of routes I was doing jumped and my technique got the chance to catch up with my tenacity and finger strength. Losing a stone and a half probably helped too! Those changes took my level to F8b, Font 8a and E8 headpoint/E6 onsight.

The main things that got me beyond that level were just tightening everything up - improving my lifestyle (more sleep and better diet), gradually building up to training 6 days a week, more variety in my climbing, sharpening up all my tactics and especially working diligently on the fingerboard to increase that finger strength foundation.

If I was 16 again I'd do little differently, my tenacity and being able to solve problems for myself and use my head are the foundation for everything else. If I'd had a home board like Malcolm, I reckon I could have got Malcolm type strength if I'd started while that growth hormone was still floating about. I definitely would have slept and eaten better, and got into trad earlier as well; more moves= more engrams =better movement. If I hadn't had those three first winters of pretty gruelling training, I don't think I would have believed I could climb hard grades. The feeling of coming outside again and pulling easily on holds that were impossible 5 months ago was such a revelation. I couldn't get enough of that feeling.

7 August 2006

Tactics - Rock-bootcamp

A deep egyptian on Devastation F8c. On this route I needed to wear different shoes on different feet as I needed a specific heel shape for the crux heelhook. (Photo: Pete Murray)

A deep egyptian on Devastation F8c. On this route I needed to wear different shoes on different feet as I needed a specific heel shape for the crux heelhook. (Photo: Pete Murray)Wearing a good quality and well fitting pair of rockshoes is so basic for rock climbing, I used to think of it as not even worth mentioning. But then I found myself telling about 50% of the climbers I've coached that they need a new pair (& different model). As I was saying in my last posts about the true basic rules of climbing technique - feet are the key. So if you hinder them by wearing boots which don't fit your foot shape, are too big so you can't put weight through your toes, or have lost all their support and are ready for the bin, you are slicing off a big chunk of your potential ability straight away. Usually, climbers using ineffective rockboots will avoid routes with small footholds, or fall of when they come across them. In my coaching sessions when we work with small footholds, the true effect of wearing the wrong shoes comes out instantly. Climbers with relatively poor footwork but good shoes can swap feet or move off small smears/edges, while climbers with good footwork flail. Unnecessary.

And maybe you think it doesn't matter in the short term, you can buy a new pair anytime right? Well it does matter - Having crap shoes you can't trust and rely on works it's way subconsciously into your technique. You start to solve move problems using your hands, because your brain subconsciously isn't trusting your feet. Once this happens, it's extremely difficult to erase. It will pull your standard down massively.

Take time to try on lots of different brands in the shop, get info about how much they stretch (it differs massively between brands). Find a pair that fit your foot shape. Watch out for what models good climbers are wearing, you can bet your life its for a reason. Ask them. And don't make the mistake of thinking something that good climbers do/use is only for good climbers.

5 August 2006

Climbing beginners - top 5 technique basics

It takes a bit of time to get comfy with being at height and moving on rock before the more detailed technical drills will help you improve. Try them in your first few sessions and they sometimes just frustrate and confuse. So here are 5 basic things to repeat in your head on your fist few sessions.

1. Feet are the key:

Your body is built to be supported by your feet. The more weight on your feet at all times, the better. When you struggle on a route, you're arms are giving in and you start to rush, think FEET - they will almost always be the reason you are stuck and the solution to keep you on the rock.

2. Arms straight:

Keep your arms straight as much as you can (i.e most of the time). The basic climbing movement is to keep arms straight, move feet into position to reach the next hold, pull up momentarily to reach next hold, arm straight again to move feet, and so on. This helps you in lots of ways but the most important benefits are reducing the muscular effort from your arms and being able to see what's going on at your feet much better than if your face is pulled hard against the wall.

3. Lots of small foot moves:

Many beginners automatically assume the making more foot moves is bad. Your footwork will become more efficient in time, but it's still normal to make 2-3 foot moves for each hand move in many types of climbing.

4. Quiet feet:

This technique has nothing to do with keeping the noise down in the climbing wall, its just a simple technique for good footwork. Avoiding jumping or scuffing your feet up the wall as you move your feet means you have to get in balance to place them carefully.

5. Make the most of each hold:

In indoor climbing, each hold will have a 'best' spot on the hold which is the part you should use. You need to try and find it (hand and feet!). Beginners tend either to grab and pull without 'feeling' for the best bit first, or, when they get stuck on a move, they feel around for way too long trying to find that magic hidden incut that isn't there. Somewhere in between is best; look and feel the hold to find the best bit, then move on. If you get stuck, concentrate your efforts on feet (see No. 1) and looking for other holds.

4 August 2006

When is the climbing 'off season'?

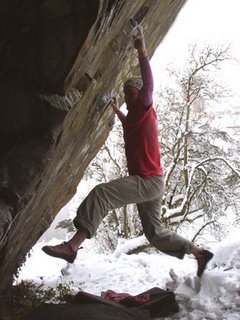

Enjoying the last of May's cold days on a project before the summer sweat comes. Hopefully by the time October comes around I'll be fit from my off season training...

Enjoying the last of May's cold days on a project before the summer sweat comes. Hopefully by the time October comes around I'll be fit from my off season training...The issue of when to go into 'off season' mode and put immediate climbing objectives aside and focus on training is always on my mind as an all round climber. We are sort of conditioned to think of summer as being the 'climbing' season and winter being the off/training season. But I noticed early on that there is really much more going on in winter.

Yeah the weather is bad, but even though there are fewer days rock climbing outdoors, the other aspects like winter climbing and indoor training all add up to mean I feel way more worn out and stretched than in summer. In summer when sport and bouldering is somewhere between a bit sweaty and unbearably hot, there is really only mountain trad to fill up large chunks of time. So about 4 years ago I switched my labels for the seasons and started doing the bulk of my foundation strength and endurance work right through summer (who needs good conditions when you are just training?).

In autumn I'll start prepping to peak and then in winter I scale down training but end up climbing 5/6 days a week (I'm lucky to live near crags, work from home and have a flexible schedule - this is obviously tricky with a 9-5). So in summer I tend not to be climbing so well as I do lots of basic strength stuff, but it doesn't matter too much since trad is a little easier technically than the equivalent overall sport grade. In winter I get loads of variety by mixing up bouldering, sport, mixed and indoor, sharpening up my technique. And conditions are good (if unpredictable but you can't have it all ways) for nailing hard projects. In summer I earn money and do basic strength training, punctuated by trips to the mountains.

I'll never look back from this set up, it works so well for me. Anyone else out there do the same?

2 August 2006

New to climbing? - the basics

One of the things I'm finding on my web crawls for good climbing training sites is a lack of god resources for beginners. My memories of getting into climbing were not being too intimidated by all these grades, ethics, rules of the sport and the jargon of training - sets, reps, intervals, Egyptians, etc I just tried to soak it up. But I know others find it off-putting. Starting out in climbing is a bit of a magical time (of course it doesn't have to get any less magical as time goes on!), and I think what you are exposed to when you start out often shapes your likes and skills later on, even if you diversify your climbing.

Strictly speaking, basic climbing safety is outwith the scope of this site, but there is certainly a lot of overlap between basic climbing tactics and skills and performance factors and they must fit together. I've added a link to the New to climbing? section for a series of Planetfear guides for starting out in various types of climbing. I'll be searching for more and writing some myself for taking your first steps in getting better at climbing once you decide you have the 'disease'.

Specific technique - feet are for pulling too!

1- Getting into position: my feet are pushing down through the footholds to support my weight, but also pulling inwards (towards the rock) to allow me to put more downward force through my feet, reducing the force on my fingers. Centre of Gravity (hips) low, arms straight. 2- Initiating the move: throwing my hips in to the wall by pulling in aggressively with my feet (note foot angle, bent legs and arms still straight).

2- Initiating the move: throwing my hips in to the wall by pulling in aggressively with my feet (note foot angle, bent legs and arms still straight). 3- exploding off my FEET using my bent legs to generate the momentum to the next hold. (side note: even though I've jumped for the hold I've maintained the tension through my body to limit the swing - note pulling in from the shoulders, forcing torso inwards and already eyeballing the next foothold and aiming for it).

3- exploding off my FEET using my bent legs to generate the momentum to the next hold. (side note: even though I've jumped for the hold I've maintained the tension through my body to limit the swing - note pulling in from the shoulders, forcing torso inwards and already eyeballing the next foothold and aiming for it).

One of my aims with this site is to focus on some of the themes I've seen to be most problematic in climbers I've coached. I'll be adding a steady flow of short tutorials on specific techniques. Please comment if you want me to write something specific that's on your mind or want me to expand on a point. Although these are designed to be applied by novice-intermediate climbers, even the best often don't use nearly the full repertoire of techniques out there. I've seen 8b climbers who don't understand the topic below.

One of the most common footwork issues I come across is that people don't realise that feet are for pulling as well as pushing and that they should be used as much like hands as possible. On overhanging rock, your COG (centre of gravity - note to self: add a training glossary/abbreviations guide to the site!) is pulling you away from the rock, reducing your ability to get weight through the footholds. In climbing getting more weight through your lower body is priority No. 1. So you have to pull (and I mean REALLY pull) inwards even on small footholds so you can get more weight on them. When I coach climbers I see this pulling and pushing at the same time idea is a little confusing at first, but once experienced/understood is always a revelation. The next stage is to find out just how hard you can pull with your feet. Legs are pretty damn strong limbs (compare the volume of your forearm to your thigh) but often people don't really use them because it feels natural to concentrate on pulling with our arms. Next time at the wall, seek out a good climber. Stand and watch them and look out for when they are pulling with their feet. Watch how they hook their big toe over the foothold, pull in and then execute the move. Now copy it.

Perspective - a culture of low standards

The national average standard for climbers in the UK is very low – VS/HVS from what I gather. Ask most climbers and they will tell you they would like to be climbing harder. You can bet a VS climber would be more likely to make it happen if 90% of climbers were at E4. It takes bit of courage to break out of the normal culture – it takes some individual thinking.

Interacting with as many people, places, habits, and resources as possible that have a ‘social norm’ that oozes a high standard of quality, performance, effort, whatever the variable, will work its way into your norms. Yes, believe is or not if you spend all your time climbing with good climbers (good in some respect, not necessarily grade, maybe just effort level) it rubs off on you without you even knowing it. It’s quite a marvellous feeling when it happens! If none of your climbing mates train, will you go and train on your own while they go to the pub? If you live in the Spanish Basque country and EVERYONE climbs 8c including the females these days, will you stick at VS? Of course there is a balance to be struck between your climbing goals compromising the places and people you spend your time with, but most peoples balance has room to shift a little. You only get one life and there are many paths through it, you might as well choose a good one.

We need more data!

Working moves on Rhapsody June 2005. I kept a training diary all summer so I made sure I didn't skip any sessions while still getting lots of days on the route (Photo: Steven Gordon)

Working moves on Rhapsody June 2005. I kept a training diary all summer so I made sure I didn't skip any sessions while still getting lots of days on the route (Photo: Steven Gordon)Well its good to see interest in this site starting to get going already - wow! In the comments for my last post Lee from Australia gave us a link to his training diaries article. Lee admits to being fanatical about training and I'm guessing very few of us keep training diaries in the long term. So should you? Well, probably yes! I only keep one for a couple of months of the year when I'm not climbing, just training specifically for something. Last year when I was training for Rhapsody I kept one for three months because I had so many training objectives to fit into the training week - fingerboard sessions, endurance circuits, flexibility, running and I was trying to get 4 sessions a week on the route itself. You might say 'well why not just allocate a weekly routine with set tasks on Mon, Tues etc..' Well yes thats fine if you can do that, but most peoples lives aren't so simple. And if you are trying to do your real climbing outdoors then you have to schedule around the weather. So all in all its easy to lose track of your volume and it inevitably slips either side of the optimum.

I tend to keep track of my yearly volume in my head because training comes first in my daily schedulea and I think about it non-stop. But for most thats not the case. If you want to improve year on year you NEED to be sure you are doing more training/climbing load than last year, otherwise your body won't adapt. The Scotland Online article on the links page has more on the overload principle. It's always an eye opener when you write down some detail on how much time you spend training - it always makes you realise just how big the gaps are at certain times of year when life gets in the way. If these gaps were smaller, a lot of people would be climbing a lot harder.

1 August 2006

Climbing training web crawl

I also ran many searches and identified many gaps in written guidance on the web, especially in our specialisms here in the UK; trad and winter climbing. So they will be my priorities over the coming weeks as I add more articles to davemacleod.com articles page. I'll also be doing some much needed interviews with well known coaches and climbers and hopefully learning some of their secrets.

If you know of any good links, or want to comment or request specific links or information, email me (my email is the first link). This is your service - use it to get better at climbing.